You head to the supermarket to pick up a box of cereal. You don’t have much idea about other brands, but you buy one because it sounds familiar—you’ve seen or heard it on television commercials or in the supermarket aisle previously. Afterwards, while driving home from the store, a song comes up on the radio. You didn’t pay much attention when you heard it for the first time, but now, since you’ve been hearing it so often, you’re singing along.

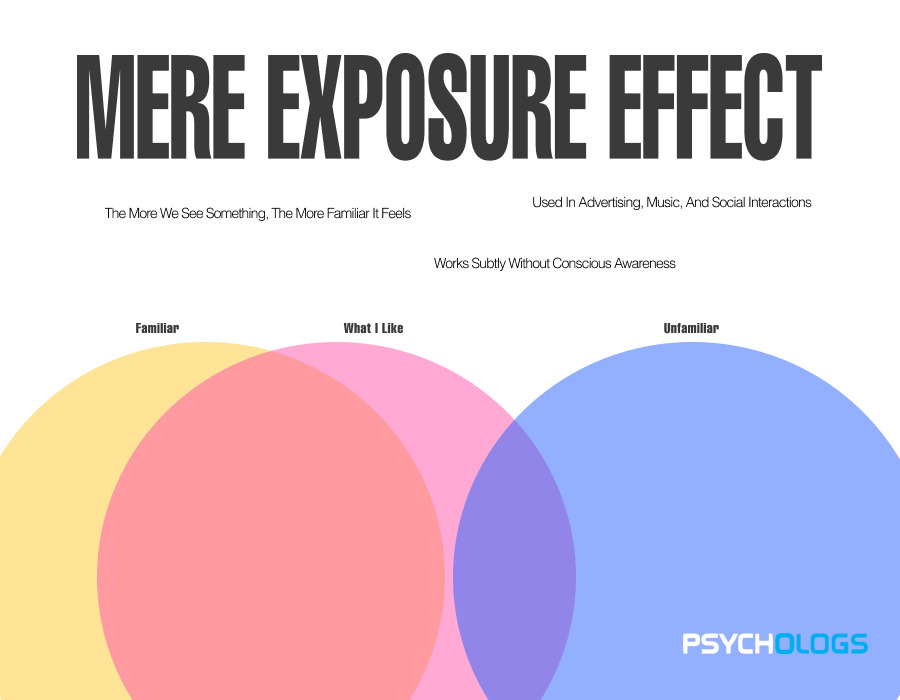

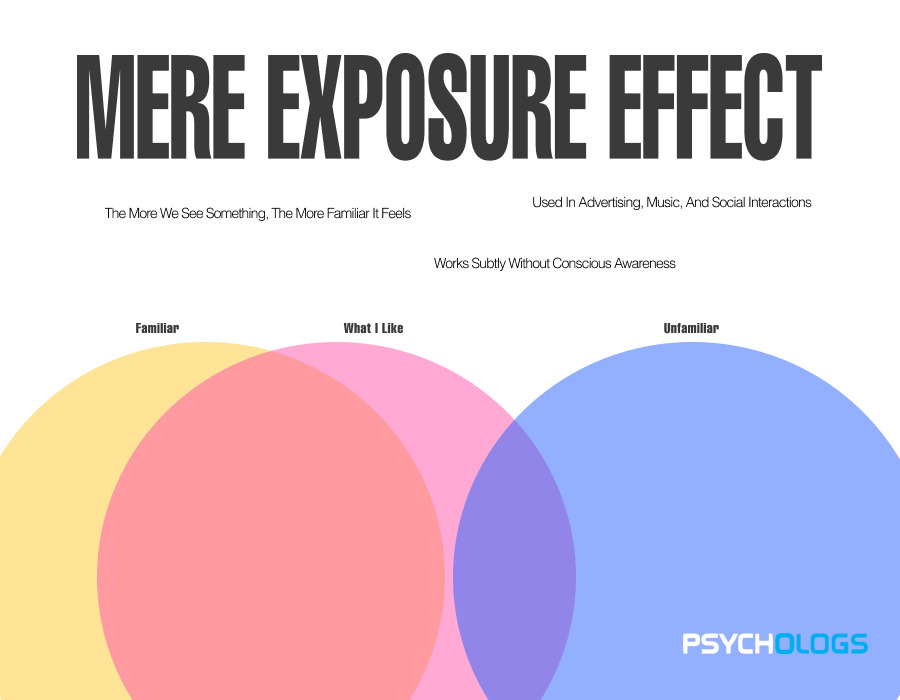

This is the mere exposure effect at work. The more we encounter something, the more we tend to like it, even if we’re not consciously aware of it. Familiarity fosters comfort, be it with a product, song, individual, or even a government official. In the background, this psychological strategy directs our day-to-day choices, from whom we trust and what we purchase to the way we vote.

How the Mere Exposure Effect Functions

The mere exposure effect was first identified by social psychologist Robert Zajonc during the 1960s. In one of his most celebrated experiments, students were shown a series of symbols, some repeatedly and others only once. When asked to describe which symbols they liked best, students consistently picked those they saw most frequently—regardless of whether they recalled seeing them (Zajonc, 1968).

This shows that just knowing something can affect preferences, even though the individual isn’t consciously aware. Over time, scientists have studied its effect in a range of domains, including marketing, relationships, and even how people vote, showing its profound effect on choice and social interactions. Several reasons have been given as to why this occurs:

1. Decreased Uncertainty

Humans are evolutionarily wary of the unknown. Research by Bornstein and D’Agostino in 1992 suggests that repeated exposure signals safety, making us feel more comfortable and positive toward familiar stimuli. This is why people often feel an immediate sense of ease when they recognize a brand or face, even if they cannot recall where they saw it before. It serves as an unconscious comfort that what we are experiencing is not threatening or entirely unfamiliar, enabling us to build positive connections. This is also the reason individuals tend to believe ideas, messages, or words they have heard repeatedly, even if they cannot identify where.

2. Cognitive Fluency

As per studies by Reber, Winkielman, and Schwarz in 1998, the more familiar something is, the more easily the brain can process it, and with less effort. This ease builds a sense of preference, with familiar options being perceived as feeling more natural. This is very significant in making decisions when individuals prefer what feels effortless or automatic.

For instance, when deciding between two similar products of coffee, we tend to choose the one we have experienced before since our minds understand it more easily, which makes it seem like the “better” option. This is not limited to consumer culture; in educational contexts, even students tend to favour ideas and concepts they have encountered before because they seem easier to understand and relate to.

3. Emotional Comfort

Familiarity may provide psychological comfort, and the stress and anxiety that go with it may decrease. That is why individuals rewatch loved films or hear known songs when they require assurance (Lee, 2001). The emotional security offered by familiarity may reach into social contexts as well—individuals are inclined towards known faces in a crowd or head to places and patterns that are familiar.

This is why numerous individuals experience a sense of nostalgia when they go back to child sites or take part in habits they have had for years because these activities are reminiscent of the reassuring feeling of belonging and security. The effect of mere exposure also contributes to social relationships because frequent interactions with an individual, even without intimate conversation, bring about a sense of familiarity and trust.

Interestingly, studies have revealed that exposure doesn’t necessarily have to be accompanied by conscious awareness. Even when individuals don’t recall having viewed something, they can still acquire a liking for it (Monahan, Murphy, & Zajonc, 2000). This indicates that exposure affects preferences at a profound psychological level, making us choose things without our knowledge.

This unconscious impact is especially true in advertising, where repeated viewing of a brand or slogan makes it more likeable and seem more credible. It also showcases how exposure can mould cultural and societal trends in the long run, as repeated messages through media and politics slowly mould public opinion.

The Mere Exposure Effect in Everyday Life

1. Marketing and Consumer Behaviour

Advertising relies heavily on the mere exposure effect. The more often people see a product, the more likely they are to buy it—not necessarily because it’s better, but simply because it feels familiar (Grimes, 2006). That is why businesses keep running the same ads over and over, put their names in strategic positions, and advertise at high-profile events. The effect is amplified when coupled with positive communications or endorsements by credible sources, as it confirms the relationship between recognition and credibility.

Even political campaigns resort to this. The more a candidate’s face is shown on TV or social media, the more popular they become—even if voters are not familiar with their policies (Schaffner & Streb, 2002). This is most clear in elections where name familiarity is a significant factor in voter choice. A voter might not have the time to study policies at length, but repeated exposure to a candidate’s name or face can build a sense of familiarity and trust, which then influences their vote.

The same phenomenon can be seen in brand loyalty, where constant exposure creates lifetime buyers who correlate a brand with quality and reliability without ever having tried others. Companies also apply this rule in product placement, getting their logos featured in mass-market movies, shows, and social media websites to quietly build customer preference over time.

2. Music, Art, and Entertainment

Ever wondered why radio stations play the same hit songs repeatedly? According to a 2004 study by Szpunar, Schellenberg, and Pliner, people are more likely to enjoy music the more times they hear it. Replaying music you’ve already heard makes you like it more, which is why streaming services make customized playlists. Cutting’s 2003 study at Cornell University proved this effect in fine arts.

Students repeatedly shown certain paintings evaluated them as more beautiful than paintings they had less frequently seen, even though they did not know consciously which ones they had been shown. This shows the power of repeated exposure in shaping our artistic tastes. Even in movies and television, repeated exposure can alter our first impressions of a character or plot. People we see all the time—in advertisements, television programs, and films—gain likability from mere exposure, even if they are unremarkable or even annoying at first.

Mere Exposure in Groups and Crowd Behaviour

Crowds tend to do things that observers find unexplainable. In 1969, Milgram and Toch’s study implied that mere exposure to a crowd can give one a sense of belonging and communal action. Crowds tend to exhibit “milling” behaviour, with individuals moving quickly from one location to another, thereby increasing their exposure to other members of the group. This subtle effect of exposure can heighten feelings of trust, similarity, and belonging and make collective action more probable.

This process is a key component of group identity and belonging. Repeated exposure to similar others in mass social movements produces a sense of solidarity, reinforcing common beliefs and motivating people to act together. This is why people feel more emotionally attached to a crowd they have spent time with, even though they do not know the people surrounding them. The mere exposure effect can also lead to mob mentality, in which individuals become more and more devoted to a cause or action simply because they are repeatedly exposed to it in a group environment.

How to Prevent Being Overly Influenced by Mere Exposure

It is not possible to entirely escape the mere exposure effect, but there are means of minimizing its influence on decision-making:

- Be Aware: Understanding that familiarity affects preferences can help overcome unconscious biases. Awareness alone can stop us from instinctively preferring familiar options without considering alternatives. By deliberately questioning our choices, we can make sure they are based on rational reasoning and not just exposure.

- Seek Diverse Perspectives: Encounter people, books, and media that oppose your current inclinations and broaden your understanding. Enriching your knowledge with varied viewpoints counteracts the mere exposure effect’s tendency to generate comfort-driven bias.

- Limit Repeated Media Exposure: Pay attention to repeated political statements, advertisements of brands, and social media that could be forming your beliefs. Social media algorithms, for example, aim at reinforcing past predilections through repeated exposure to similar information, so diversify sources of information.

- Challenge Yourself: Experiment with new things—try different music, venture into foreign cuisine, and take in new perspectives. The more we learn about new experiences and ideas, the less prone we are to fall into making decisions based only on familiarity. This is critical in a media-driven world in which existing taste is reinforced consistently through targeted programming.

Conclusion

The mere exposure effect influences human behaviour in significant ways, from what we purchase to whom we trust. This effect is typically a positive one—enabling us to make friends, acquire skills, and relax in comfortable situations. It also causes biases and manipulation. With a knowledge of how repeated exposure affects preferences, people can become more aware and informed in the areas of relationships, consumer behaviour, and politics. Being aware of this allows people to exercise greater control in making decisions, making sure our preferences are a result of actual interest and not simply familiarity.

Read More From UPS Education

- The Five Stages of Memory

- Self-Determination Theory

- Psychology of Deception

- Loss Aversion Explained: What Shapes Our Fear of Losing?

FAQs

1. What is the mere exposure effect?

The “mere exposure effect” is a psychological effect in which individuals enjoy something because they know it. The effect can be employed when making choices in entertainment, politics, relationships, and advertising.

2. Why do we like something more when we are exposed to it again and again?

Familiarity reduces ambiguity, increases our capacity to process information and makes our affective distress more bearable. Through repeated exposure over time, we develop a positive attitude toward the object, person or idea even when we are unaware of past experiences.

3. How does the mere exposure effect influence consumer behaviour?

Repeated exposure, brand salience, and logo salience are used by companies to make people familiar with what they sell. People purchase recognizable brands, rather than because of their superiority, but because they are more familiar with them.

4. Can political decisions be made by the mere exposure effect?

In fact, political campaigns take advantage of this phenomenon by repeatedly showing a candidate’s face, name, or motto. People can end up preferring familiar candidates even if they are not consciously aware of their policy or qualifications.

5. How does the mere exposure effect affect entertainment tastes?

The more we hear a song, see a character in a movie, or view a painting, the more we enjoy it. This is the reason radio stations rotate hits over and over and why others enjoy movies or television programs more upon repeated viewings.

6. Is the mere exposure effect likely to produce biases or misinformation?

Indeed, the mere exposure effect is essentially a result of repeated exposure to certain ideas, opinions, or news—often via social media algorithms. People may believe something simply because they’ve heard it repeatedly when it is actually not factually true.

7. How do we limit the influence of the mere exposure effect on our decision?

Being aware of this bias, seeking diverse views, questioning default choices, and not being subjected to repeated commercials or television programs can minimize its unconscious influence on decisions.

References +

- Bornstein, R. F. (1989). Exposure and affect: Overview and meta-analysis of research. Psychological Bulletin. 10.1037/0033-2909.106.2.265

- Cherry, K. (2023). Mere exposure effect: How familiarity breeds attraction. Verywell Mind. https://www.verywellmind.com/mere-exposure-effect

- 7368184#:~:text=The%20mere%20exposure%20effect%20refers,or%20even%20pote ntial%20romantic%20partners

- Fang, X., Singh, S., & Ahluwalia, R. (2007). An examination of different explanations for the mere exposure effect. Journal of Consumer Research. https://doi.org/10.1086/513050

- Lee, A. Y. (2001). The mere exposure effect: An uncertainty reduction explanation revisited. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672012710002

- Milgram, S., & Toch, H. (1969). Collective behavior: Crowds and social movements. The handbook of social psychology.

- Monahan, J. L., Murphy, S. T., & Zajonc, R. B. (2000). Subliminal mere exposure: Specific, general, and diffuse effects. Psychological Science. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467- 9280.00289

- Moreland, R. L., & Beach, S. R. (1992). Exposure effects in the classroom: The development of affinity among students. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(92)90055-o

- Moreland, R. L., & Levine, J. M. (1989). Newcomers and oldtimers in small groups. Psychology of group influence.

- Nanay, B. (2024). The mere exposure effect in politics. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/psychology-tomorrow/202405/the-mere exposure-effect-in-politics

- Nickerson, C. (2023). Mere exposure effect in psychology: Biases & Heuristics. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/mere-exposure-effect.html

- Pilat, D., & Krastev, S. (n.d.). Why do we prefer things that we are familiar with?. The Decision Lab. https://thedecisionlab.com/biases/mere-exposure-effect

- Reis, H. T., Maniaci, M. R., Caprariello, P. A., Eastwick, P. W., & Finkel, E. J. (2011). Familiarity does indeed promote attraction in live interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022885

- Stafford, T., & Grimes, A. (2012). Memory enhances the mere exposure effect. Psychology & Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20581

- Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9(2, Pt.2), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0025848

- Zebrowitz, L. A., White, B., & Wieneke, K. (2008). Mere Exposure and Racial Prejudice: Exposure to Other-Race Faces Increases Liking for Strangers of that Race. Social Cognition. https://10.1521/soco.2008.26.3.259

Leave feedback about this