For a few decades now, the gut-brain connection has been an exciting topic of research in biopsychology and nutritional psychiatry. At one time, these two systems might have been approached as separate entities, but now it is known that the gastrointestinal tract forms a communication pathway with the central nervous system in a bidirectional fashion. This axis is instrumental in mental health, indicating that what we choose to eat can influence the very core of our emotions and our very behaviour; in fact, even psychological disorders are suggested to be influenced. We discuss the biopsychological mechanisms behind the gut-brain connection, the role diet and microbiome might play, and how treatment or prevention strategies may work concerning mental health.

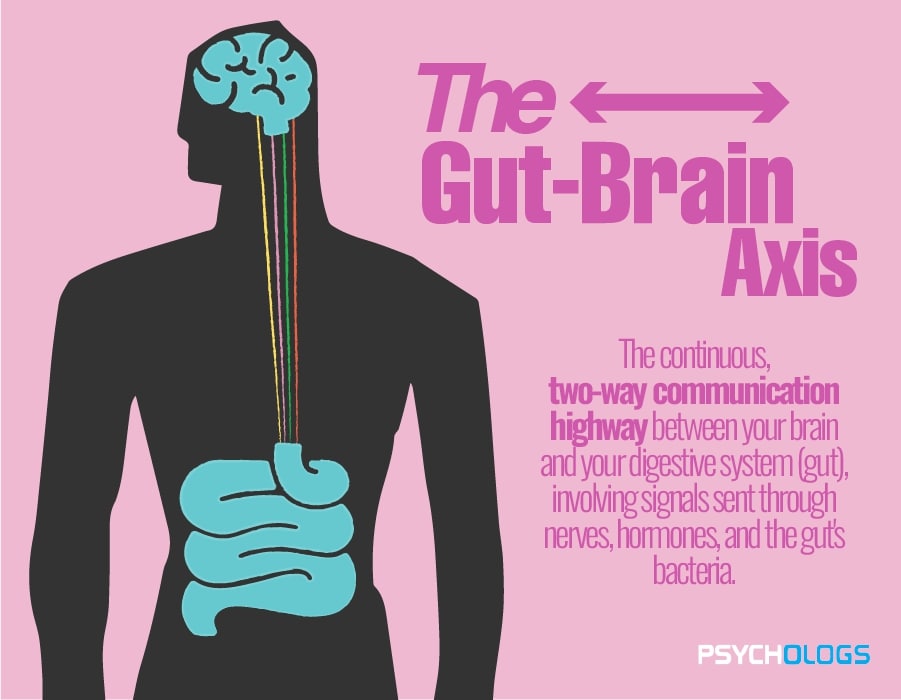

Defining the Gut-Brain Axis

The term gut-brain axis refers to the dynamic, two-way communication between the central nervous system (CNS) and the enteric nervous system (ENS)—which provides a web of millions of neurons spread along the gastrointestinal lining. The communication occurs through:

- Neural paths (i.e., vagus nerve)

- Endocrine signaling (hormones such as cortisol and serotonin)

- Immune factors (cytokines)

- Microbial metabolites (short-chain fatty acids)

The vagus nerve, central to this mechanism, conveys messages from the gut to the brain and back. Such communication also involves hormones, of which are ghrelin, leptin, and cortisol, that affect the brain’s perception of hunger, satiety, and stress. Inflammatory responses, which may be mediated further by cytokines and other immune signaling molecules, are known to exert influences over mood and cognition.

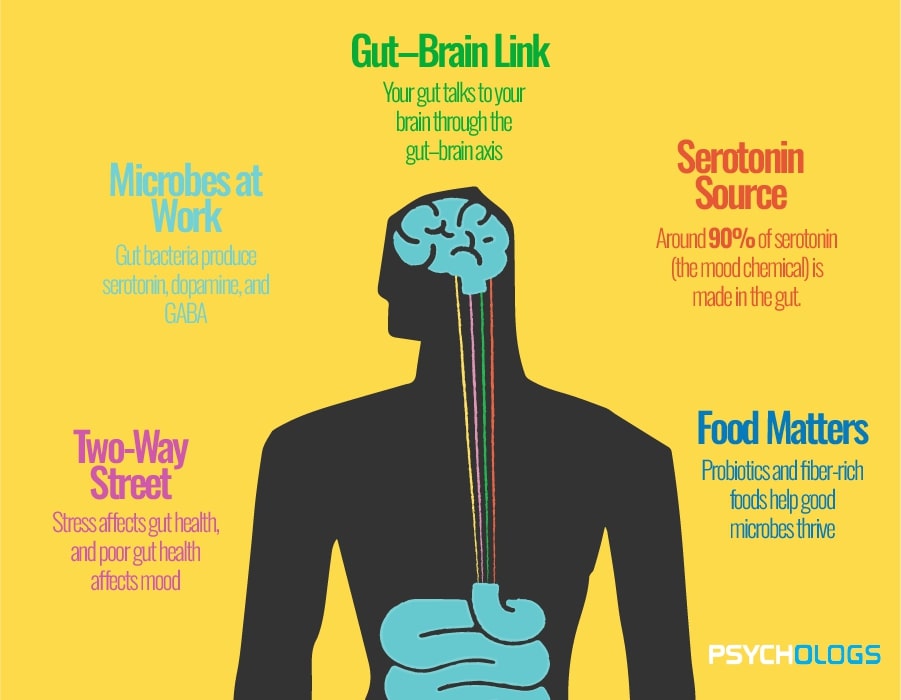

Microbiota: The Gut’s Invisible Brain

There are trillions of microorganisms festering away inside the human gut, together known as gut microbiota, playing a major role in health and disease. This microbiota aids digestion, fine-tunes immune functionality, and synthesises some nutrients and neurotransmitters.

- Neurotransmitters produced by the gut bacteria:

- Serotonin: 90-95% of this neurotransmitter is produced inside the gut. (Terry & Margolis, 2016)

- GABA (Gamma-aminobutyric acid): A decrease of neuronal excitation, it’s also correlated with anxiety regulation.

- Dopamine: Motivation and reward are interlinked with this neurotransmitter.

Dysbiosis states in the microbiome have been speculated to associate with anxiety, depression, autism spectrum disorder, and schizophrenia. Conversely, a healthy microbiome could potentially maintain mental health through the production of anti-inflammatory substances and neuroactive substances.

Diet and the Influence on the Gut-Brain Axis

The diet is a major mediator of the biopsychological pathway between diet and mental health. Microbial diversity and metabolic functions are altered, depending on food choices; hence, brain activity varies accordingly.

1. Western versus Mediterranean Diet

Western-diet-type population studies suggest gut dysbiosis and inflammation, and depression. Mediterranean diets favour microbiota diversity and are associated with the relief of depressive and anxiety symptoms. Higher in fibre, fruits, vegetables, legumes, and healthy fats, the landmark SMILES trial showed that patients diagnosed with major depressive disorder placed on a Mediterranean-style diet with medical nutrition therapy had marked improvements in mood compared to controls receiving social support. (Jacka et al., 2017)

2. Fibre and Prebiotics

Fibres are nourishment for the good bacteria and, consequently, are good prebiotics, for example, food components like inulin and fructooligosaccharides. Bacteria that use such prebiotics, therefore, produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as butyrate, acetate, and propionate, which can:

- Strengthening of the intestinal barrier

- Modulation of immune response

- Brain signalling through systemic circulation or the vagus nerve

3. Probiotics and Psychobiotics

As per convention, probiotic microorganisms are considered to be agents providing clinically proven benefits on the host; recently, the label of psychobiotic has been put forth for those whose benefits also include effects on mental health. Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species are considered beneficial for anxiety and depression.

Stress, Inflammation, and the Gut

Chronic psychological distress can eat away at the structure of the gut lining and disrupt the gut microbiota population. Through such disruptions, the so-called intestinal arcade “leaky gut” is developed, and in doing so, germs and toxins might pass into the bloodstream, leading to various inflammations. Almost all psychiatric disorders have inflammation as a relatively consistent concomitant feature: In other words, a depressed person is usually characterised by a set of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNF-α. This form of inflammation affects neurogenesis, synaptic plasticity, and neurotransmitter metabolism.

Here, the diet gives protection. For example, antioxidants, polyphenols, and omega-3 fatty acids present in foods like walnuts, turmeric, and berries can curb inflammation and oxidative stress, thereby protecting mood and cognition.

Psychological Disorders and Gut Microbiome

1. Anxiety and Depression

There have been increasing numbers of indications that Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is related to alterations in gut microbial contents. Patients diagnosed with MDD have a decrease in microbial diversity, and the number of bacteria is diminished; among such bacteria considered as helpful are Coprococcus and Faecalibacterium, which have been tied to the production of short-chain fatty acids. The interaction with the gut includes treatments such as probiotics, fermented foods, and diet, which appear to help in reducing mood and anxiety symptoms.

2. ASD, or autism spectrum disorder

Children with autism often experience gastrointestinal issues, and studies suggest a link between gut bacteria and behavioural symptoms. Alterations in the gut microbiome may influence social behaviour, cognition, and repetitive behaviours, although the mechanisms are still being explored.

c. Schizophrenia

Recent studies state that gut bacteria may regulate glutamatergic and dopaminergic transmission associated with schizophrenia. Microbial metabolites can subject patients to oxidative stress and an inflammatory response.

Lifespan and Developmental Considerations

The gut-brain axis is a continuous, ever-evolving phenomenon that evolves with life:

- Childhood: Microbial colonization and possibly even cognitive development can be influenced by early feeding practices, breast milk, and vaginal versus C-section birth.

- Adolescence: This stage is critical for brain development and is very susceptible to dietary changes due to constitutional factors.

- Ageing: Decreased microbial diversity and increased inflammation (inflammaging) are two effects of ageing that may also be linked to dementia and cognitive decline.

Physical, cognitive, and emotional resilience are therefore dependent on gut health being maintained throughout life.

Therapeutic Applications and Future Perspectives

- Nutritional Psychiatry: It concerns the emerging field of interventions based on diet to treat mental illness. While these methods do not substitute the use of medication or psychotherapy, nutrition may offer an inexpensive, low-risk supplement.

- Personalised Nutrition: By way of advances in metagenomics and microbiome profiling, diets will be personalised at the individual level based on one’s microbiome profile and mental health conditions.

- Faecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT): Still experimental, FMT shows a lot of promise in the treatment of some pathologies like Clostridioides difficile infection, being even proposed for psychiatric-metabolic disorders, including treatment-resistant depression.

Conclusion

The gut-brain axis essentially suggests a revolutionary idea: mental health depends on and revolves around what happens in the gut. Through the gut microbiome, dietary elements, exocrine secretions, and immune processes, our digestive glands might work on thinking, feeling, and overall mental health. This new understanding has changed the boundaries of considered mental healthcare-working towards holistic care encompassing the gut and brain together.

In the past, mental health would talk about drugs and therapy. Psychopharmacology and psychotherapy are very important, really. But now, having gotten the lay of the land of modern gut-brain science, we can add a third, more powerful and fundamental element to the foundation of mental well-being: nutrition and biological systems. So mental health is not just about thoughts and behaviour; it also has a lot to do with biology, with inflammation, metabolism, and with the organisms that we live with.

The big picture is fascinating: Disorders in the gut may be at the root of or may aggravate many psychological conditions, including depression, anxiety, neurodevelopmental disorders, and cognitive ageing. Meanwhile, easily accessible options might go a long way to restore balance-having more fibre in the diet, eating fermented foods, reducing sugar intake, and supplementing with probiotics might be at the forefront of prevention strategies, as well as clinical adjuncts.

The gut-brain axis is essentially a dynamic feedback loop. Stress and disturbed sleep can wreak havoc on the gut, whereas an already distressed gut can aggravate one’s stress level and interfere with sleep further. Through this bilateral channel, lifestyle factors such as mindfulness, exercise, sleep hygiene, and hydration could offer a psychological effect by altering gut activity and microbiota composition. It follows that one’s gut health is an area in which a series of good habits converge.

This field is exciting because it is interdisciplinary. With neuroscience, psychology, nutrition, gastroenterology, and immunology coming together to study the gut-brain axis, the convergence of these fields explores new frontiers in psychobiotics, microbiota-based therapies, faecal transplants, and customised nutrition plans. When these new interventions become more refined and widely available, a paradigm change could take place in mental health care, which involves individualised, integrative care for treating the mind and gut as co-dependent systems.

Stretching a bit, but the sciences are still damp. Not every person reacts to microbiome-related therapies in the same way, with the intricate communication between the gut and brain still needing more elucidation. Genetics, environment, lifestyle, and medication history: We are talking about a lot of factors, all influencing the way each individual responds to any dietary or probiotic intervention. As researchers dive deeper into uncovering the subtleties, yet more diagnostic tools and treatment regimens are expected to be developed.

Nevertheless, the immediate solution is: the gut has to be supported, perhaps being one of the best things that can be done for one’s mind. A happy gut can bring about emotional resilience, cognitive sharpness, reduced anxiety, and elevated self-esteem. While it certainly cannot heal every ailment, gut care stands to offer a solid foundation upon which mental well-being may blossom. One can change his or her digestive health by eating mindfully, stressing less, sleeping well, and trusting their gut to bring forth a deeper emotional equilibrium, mental clarity, and inner resilience

FAQs

Q1: What is the gut-brain axis?

However, the gut-brain axis is a two-way communication system between your brain and gut. The pathways in this axis involve the nervous system, particularly the vagus nerve, hormones, the immune system, and gut microorganisms. This connection controls mood, emotions, stress levels, and even cognition.

Q2: How can the gut microbiome influence mental health?

Microbes in the gut produce neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, and GABA, which are essential contributors to mood regulation. An unhealthy gut microbiome, also called dysbiosis, has been linked to anxiety, depressive states, and the inability to focus or think clearly.

Q3: Will diet forcefully influence mental health?

Yes. High-fibre diets and intestinally beneficial fats, as well as rows of fruits and vegetables and fermented foods, feed the gut microbiome, which in turn supports mental well-being. So-called poor diets, that is, those over sugars and processed foods, increase inflammation and the risk of mental disorders.

Q4: What are probiotics and prebiotics, and how do they help?

Probiotics consist of live beneficial bacteria present in yoghurt, kefir, kimchi, and so on. Prebiotics are fibres that nourish beneficial bacteria and can be found in garlic, onion, and bananas. Both can support a well-functioning gut microbiome, potentially elevating mood and reducing anxiety.

Q5: Is there scientific evidence on this gut-brain connection?

Yes, there is. Several studies—including the landmark SMILES trial and much research into the microbiome—show strong correlations between gut health and mental health outcomes. Research is ongoing in the field of nutritional psychiatry and continues to support these findings.

References +

- Dawson, S., Dash, S., & Jacka, F. (2016). The importance of diet and gut health to the treatment and prevention of mental disorders. International Review of Neurobiology, 325–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.irn.2016.08.009

- Ma, L., Wang, H., & Hashimoto, K. (2024). The vagus nerve: An old but new player in brain–body communication. Brain Behaviour and Immunity. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2024.11.023

- Philadelphia, C. H. O. (n.d.). Food as medicine: Prebiotic foods. Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. https://www.chop.edu/health-resources/food-medicine-prebiotic-foods

- Philadelphia, C. H. O. (n.d.). Food as medicine: Prebiotic foods. Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. https://www.chop.edu/health-resources/food-medicine-prebiotic-foods

Leave feedback about this