Memory is strange. We suddenly remember random jingles from childhood ads. And then there are times when we meet someone and instantly forget their name. This can be quite perplexing. Why does this happen? What makes some information stick while the rest of it just disappears into the void?

Turns out, memory is not just our mind’s filing cabinet where information gets neatly stored away. Memory is a complex mental process that is ever-changing. Psychologists break this process down into five main stages. They are encoding, consolidation, storage, retrieval and lastly, forgetting. Every piece of information we encounter moves through these stages. The process, on the whole, determines what we remember and what we don’t. So, what exactly happens at each stage?

Encoding

Encoding refers to the initial processing of information so that it can be represented in memory. It is the first step in creating a new memory. Encoding influences how well we retain and retrieve information later.

Every day, our brain deals with a flood of information. And, at the end of the day, only some of it remains. This is because not all encoding is equal. Craik and Lockhart’s (1972) Levels of Processing theory suggests that the depth at which we process something determines how well we remember it. According to this theory, there are three levels of processing: shallow, intermediate and deep. A glance at something would be considered shallow processing. But when we connect new knowledge to what we already know, for example, we process it at a deeper level.

The type of encoding also matters. Visual encoding involves forming mental images, like remembering a diagram from a textbook. Acoustic encoding relies on sound. For example, a catchy song lyric getting stuck in your head is acoustic encoding. But the most powerful of all is semantic encoding, which involves understanding meaning. Bower and Winzenz (1970) demonstrated this in an experiment where participants remembered word pairs far better when they imagined them interacting. For instance, imagining a dog riding a bicycle was far more memorable than simply reading “dog” and “bicycle.” So, the more meaning we give information, the harder it is to forget it. The way information is organised during encoding is important.

Storage

As soon as any information enters our memory, it enters our mind’s storage system.

Atkinson and Shiffrin’s Multi-Store Model (1968) suggests that it contains three components. Sensory memory briefly holds raw information from our environment, just for a few seconds. When we focus on it, some of this data moves to short-term memory (STM). Here, it lasts for 15–30 seconds unless rehearsed. Meaningful information then transfers to long-term memory (LTM) through a process called elaborate rehearsal. Memories can remain in the LTM indefinitely.

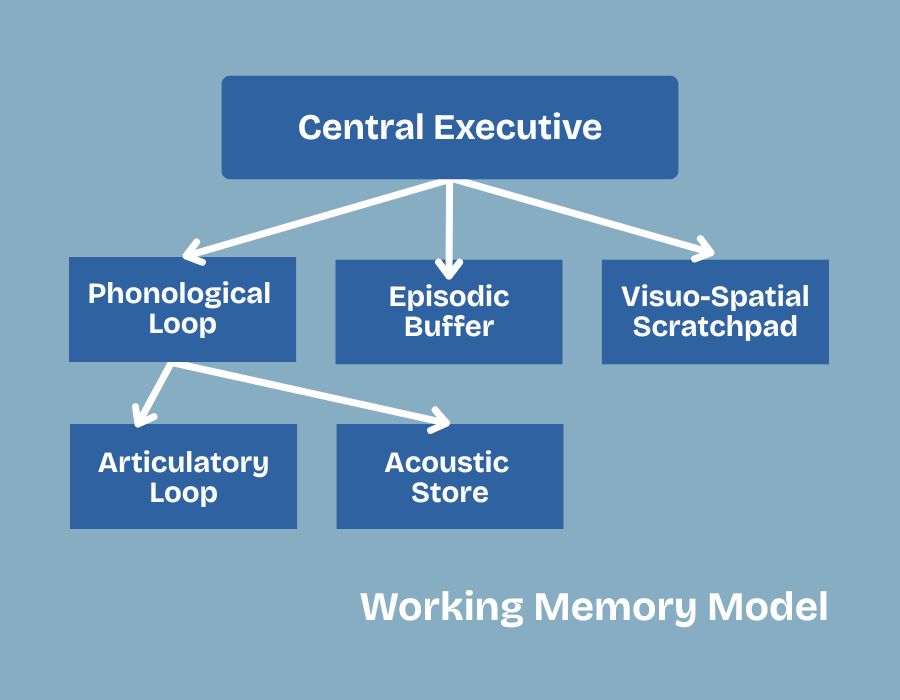

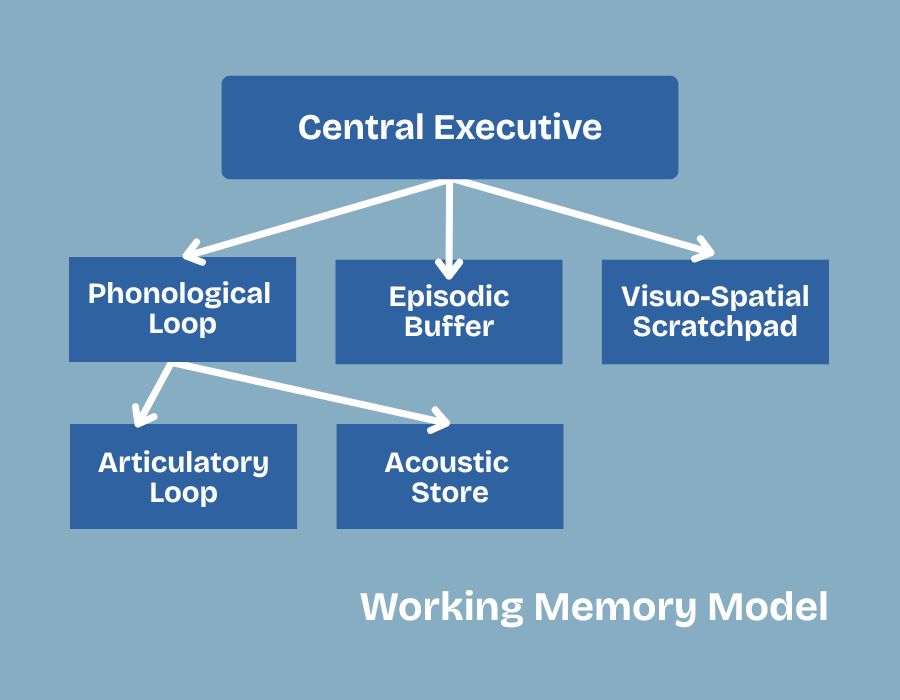

Expanding on this, Baddeley and Hitch (1974) proposed the working memory model. This model views STM as an active system with three components: the phonological loop (which processes sounds and words), the visuo-spatial sketchpad (which handles images and spatial details), and the central executive (which manages attention and coordination). This explains how we process multiple types of information at once.

Long-term memory isn’t a single entity. Tulving (1972) divided it into explicit and implicit memory. Explicit memory includes episodic memory (personal experiences) and semantic memory (general knowledge). Meanwhile, implicit memory (skills and habits) operates unconsciously and relies on structures like the basal ganglia and cerebellum rather than the hippocampus.

But storing a memory is only the beginning. For it to last, it must be consolidated.

Consolidation

Memory consolidation is the process by which memories become more stable and resistant to disruption over time. It’s a crucial process to ensure lasting, long-term memories. Consolidation happens in two phases.

Firstly, synaptic consolidation occurs a few hours after learning. Here, neurons strengthen their connections through long-term potentiation (LTP). LTP is where repeated neural activity enhances synaptic efficiency. Essentially, stronger connections between neurons make memories less susceptible to immediate forgetting.

The second phase is systemic consolidation. While synaptic consolidation does the groundwork, systemic consolidation ensures the long-term stability of memories. Over time, memories are gradually transferred from the hippocampus to the neocortex. Here, they get integrated with existing knowledge. This way, memories are less dependent on the hippocampus, so the risk of forgetting also lessens. Sleep plays a huge role in this process. Research suggests that REM sleep, in particular, strengthens connections between related ideas.

Arousal also helps strengthen memories, especially emotional ones. Research by Kleinsmith and Kaplan (1963) shows that while high-arousal memories may be hard to recall at first, they become clearer over time.

Retrieval

Retrieval is the process of accessing stored information when needed. It enables us to bring memories into conscious awareness.

Retrieval cues help unlock memories by triggering associated information. Tulving and Pearlstone (1966) showed that people recalled more words from a list when given category cues, like “fruits” or “occupations.” This suggests that memories are organized in networks, where connections between ideas strengthen recall.

One important factor in retrieval is context. The Encoding Specificity Principle (Tulving & Thomson, 1973) suggests that memories are easier to access when conditions match those during encoding. So, if you study in a quiet room, you might recall information better in a similar environment. Even sensory cues, like a particular scent or background music, can similarly trigger recall.

State-dependent memory plays a role, too. Goodwin et al. (1969) found that people who learned something while intoxicated recalled it better when drunk again than when sober. While not practical advice, it highlights how mental and physiological states influence memory. Similarly, mood-congruent memory explains why happy moments bring happy memories to mind, while sadness makes past sorrows feel more vivid.

While retrieval is crucial, it isn’t always successful. Some memories fade, while others become harder to access without the right cues. This leads us to the final stage.

Forgetting

Forgetting is the inability to retrieve previously stored information. Forgetting might seem frustrating, but it’s not always a bad thing. It plays a crucial role in how our brains manage information. How can we make sense of how we forget?

One explanation is Decay Theory, which suggests that memories weaken over time unless revisited. But time alone isn’t the issue. Interference Theory explains how new and old memories clash. Proactive interference happens when old habits block new learning. Retroactive interference is the opposite, where new information replaces old information.

Sometimes, forgetting is intentional. Motivated forgetting (Freud, 1915) suggests distressing memories can be suppressed, though research by Loftus (1993) questions whether they’re truly hidden or falsely reconstructed. Often, memories aren’t lost but inaccessible. Without the right cue, they feel out of reach. That’s why retrieval failure can mimic forgetting. But practice and rehearsal strengthen recall. Linton (1975) found that memories fade rapidly without reinforcement, but those we revisit often stay intact.

How Does Knowing This Help Us?

Understanding how memory works has numerous real-world applications across multiple domains, from education to legal systems and aging research.

Education and Learning

Memory research has transformed how we approach studying and instruction. Spaced repetition, first identified by Ebbinghaus (1885), improves long-term retention by spreading learning over time rather than cramming. Similarly, elaborative interrogation, which involves asking “why” while studying, enhances memory by strengthening connections between new and existing knowledge. These principles help students, educators, and even professionals retain complex information more effectively.

Eyewitness Testimony and the Legal System

Memory isn’t always perfect. Loftus and Palmer (1974) demonstrated how leading questions can distort eyewitness recall, making testimony unreliable. Their findings have influenced courtroom procedures, leading to reforms in how police conduct interviews and how jurors evaluate memory-based evidence.

Memory and Aging

Aging affects memory in distinct ways. Episodic memory, responsible for personal experiences, declines over time. On the other hand, semantic memory, which stores general knowledge, remains relatively stable (Park et al., 2002). This insight has guided cognitive training programs designed to help older adults maintain mental sharpness, emphasizing lifelong learning and adaptive strategies.

Conclusion

Every stage, from encoding to forgetting, shapes how we learn and recall. By understanding how memory works, we can strengthen it with different memory-enhancing strategies.. By recognizing its limitations, we can navigate distortions, aging, and forgetting. By applying memory science, we can enhance learning, refine legal practices, and support cognitive well-being.

FAQs

1. Why do we forget things so easily?

Forgetting happens because of interference, retrieval failure, or even because our brain actively discards less relevant information. And not all memories are meant to last Our brain prioritizes what seems most useful.

2. How does sleep affect memory?

Sleep, especially REM sleep, plays a crucial role in memory consolidation. It strengthens connections between related ideas and helps transfer memories from short-term to long-term storage.

3. What are the best ways to improve memory?

Deep processing, spaced repetition, and sleep all help strengthen memory. Engaging with information meaningfully, like connecting new ideas to existing knowledge, also improves retention.

References +

- Baddeley, A. D. (1999). Essentials of human memory. In Psychology Press eBooks. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203345160

Leave feedback about this