While many animals are involved in mimicry, humans are the best. Some earlier thinkers suggested that our ability to imitate was related to our ability to have empathy and recognize what others are thinking, but for much of our advancement, we didn’t have an understanding of the relationship between imitation and empathy, nor did we completely understand what was happening in the brain. Recently, there has been more consensus about imitation from multiple perspectives of what we know about how humans behave in social situations and what the scientific evidence tells us about the brain.

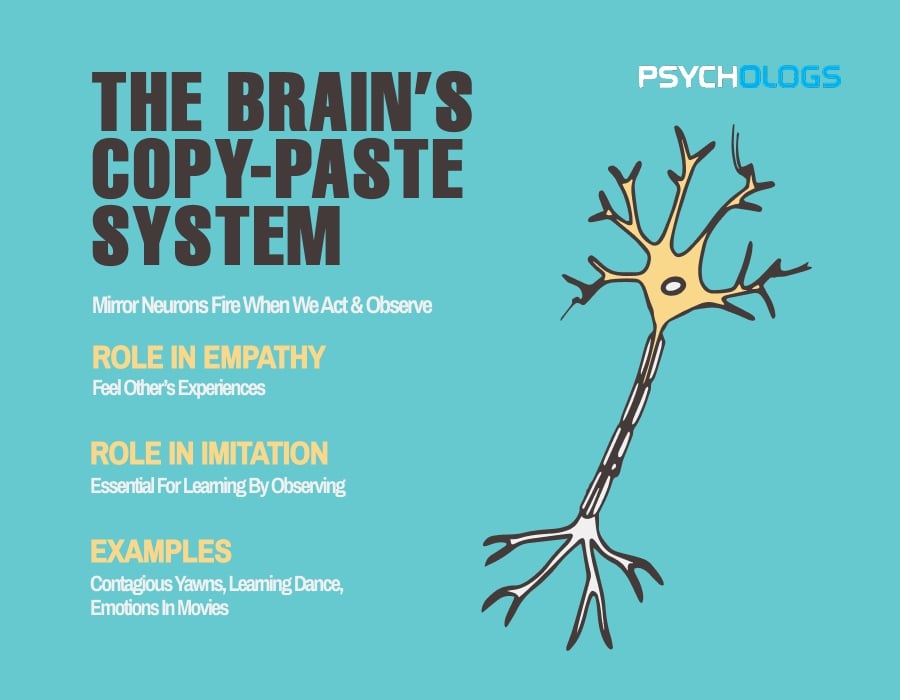

The relationship between imitation and empathy has become clearer because separate ideas and actual evidence are supportive of the other (Lacoboni, 2008). Think of your brain and your special spots that are all a part of a very special team that help you identify what other people are doing, and sometimes, at the same time, you might even imitate them (these are also known as the “mirror neurons.”)

You can find these special “mirror neuron” spots in the front (ventral premotor cortex, area F5) and, subsequently, a little to the back on the side (inferior parietal lobule, areas PF and PFG). Monkeys also have them! These “mirror neurons” are not acting in isolation but rather together with the rest of the “mirror neuron” team that exists in your brain. It’s as if these brain areas are tuned in to.

Imitation and Empathy: A Growing Scientific Consensus

Humans, while occurring in the company of many others, are best at mimicry. Some early thinkers suggested that our ability to imitate was related to our ability to empathize and be aware of other people’s mental states, yet, through much of human evolution, we did not know what the relationship was between imitation and empathy, nor did we even truly know what was going on in the brain.

Instead of discussing what we know about imitation and what the scientific evidence suggests about the brain, we can now speak more universally about imitation from various perspectives of how we know humans behave in social situations and what the scientific literature suggests about brain evidence. We have developed a better understanding of imitation and empathic behaviors, as separate ideas, that each point to the same evidence (Lacoboni, 2008). Think of your brain and your special brain locations that are part of a very special team to help you recognize what other people are doing, and at times, you might even imitate them (also called the “mirror neurons”). You may find the special “mirror neuron” brain locations in the front (ventral premotor cortex, area F5) and then a little further back on the side (inferior parietal lobule, areas PF and PFG).

Meet the Mirror Neurons: Brain’s Social Connectors

This “high road” imitation influences memory, too. In another experiment, people were asked questions about elderly people, which made that stereotype accessible in their minds. Other folks were asked questions about college students. Then, everyone was shown a desk of objects and later asked to recall those objects. Those whose brains had been “primed” with elderly stereotype recalled fewer objects than everyone else. This suggests that the activated stereotype biases their memory without conscious awareness (Dijksterhuis et al. 2000). Some people think that the “mirror neuron system” (MNS) – an assembly of brain cells – is critical for feeling what others feel – i.e., having empathy. The article discusses three main arguments that people use in support of this idea:

- How we act and feel: Do people who are good at copying others also tend to be more empathetic in studies?

- Brain scans and feelings: When people feel empathy, do brain scans show their MNS lighting up more? And do folks who say they’re more empathetic on surveys also have more MNS activity?

- Autism and copying/feeling: People with autism sometimes have trouble copying others and seem to have different experiences with empathy. Does this point to the MNS being the link? (Baird, 2011)

What happens when parts of the brain linked to copying and feeling get damaged?

The confusion lies in the fact that it appears that the MNS are involved in general empathy, whereas there are varieties of empathy and variety in MNS. For example, you may empathize by feeling someone’s pain, thinking about their actions, or even mimicking their movements. This is similar to imitation; you may imitate someone’s feelings, actions you have not thought about, or actions you have selected to engage. Thus, the relationship between both imitation and empathizing may vary depending on not only what kind of imitation you are using but also what type of empathy you are referring to.

Moreover, the brain may recruit similar or different brain regions for each of the skills we use, and therefore, the MNS may or may not be involved. From a scientific perspective, this article describes how we vary in our ability to perceive the intentions of others, dependent on some recent psychology literature, and then relate that to a specific variety of empathy that is claimed to be linked to the “mirror neuron system” (MNS). The essay will then provide a very brief overview of the scientific evidence that provides a rationale for believing the MNS is involved in empathy. The essay cautions, however, to be clearer on what the term empathy means when using the term MNS. These points about needing to be specific will lead us into the philosophical aspects of this topic.

Are Mirror Neurons Behind Empathy?

Nonetheless, this does not imply that empathy cannot be a distinctive way of knowing. The essay argues that the scientific evidence we have of mirror neurons may provide support for this idea, at least when we discuss primitive forms of empathy (Corradini, 2013). The ability to predict how other individuals think or feel is critical to achieving harmony in a social world. Social animals, particularly group-living, social primates like monkeys and apes, developed ways to display their emotional states and understand the emotional states of others. Many scientists argue that “mirror neurons” or at least some form of “mirroring” that takes place in our brains may be able to account for some basic forms of empathy.

The mirror neurons that fire in response to seeing a person’s mouth move or our temporal lobe’s automatic adaptation of facial expressions likely play an important part in an emotional connection to others. Although learning what it means to feel someone’s feelings in our own body does not explain the entire picture of empathy, it is a basic way to illustrate how we can have shared emotional states and the possibility of when these processes developed (Debes, 2017).

FAQs

Q.1 Where are Mirror Neurons located in the brain?

In humans, mirror neurons are primarily found in a network of brain regions that includes:

- Ventral Premotor Cortex (vPMC): This area is located in the frontal lobe, in front of the primary motor cortex. It’s involved in planning and executing movements and contains neurons that fire both when you act and when you see someone else perform a similar action.

- Inferior Parietal Lobule (IPL): Located in the parietal lobe, behind the sensory cortex, the IPL is involved in integrating sensory information and plays a role in understanding spatial relationships and processing actions. Mirror neurons here also fire during both action execution and observation.

These two areas, the vPMC and the IPL, are considered the core of the human mirror neuron system. However, research suggests that other brain regions may also exhibit mirror-like activity, including:

- Supplementary Motor Area (SMA)

- Primary Somatosensory Cortex

- Inferior Frontal Gyrus (IFG) – which includes Broca’s area, important for language

- Superior Temporal Sulcus (STS) – involved in perceiving biological motion

It’s important to remember that the exact extent and function of the human mirror neuron system are still areas of active research.

Q.2 When are Mirror Neurons active?

Mirror neurons are active both when an individual acts and when they observe another individual performing the same or similar action. This activity is thought to play a role in understanding others’ actions, intentions, and potentially empathy.

Q.3 How do mirror neurons affect emotions?

Mirror neurons are like our brain’s way of “feeling with” other people. When we see someone showing an emotion like being happy or sad, these special brain cells fire up in our brain. It’s almost as if we’re feeling that emotion ourselves, even though we’re just watching. This “mirroring” helps us understand what others are feeling and is a big part of empathy and how we connect socially.

Read More from Us

- Perceptual Processing

- Synaptic Transmission: How Information Travels in the Brain

- Placebo vs. Nocebo: Can Belief Heal Or Hurt You?

- The Role of Schema in Cognitive Development and Its Impact on Psychology

References +

- Baird, A. D., Scheffer, I. E., & Wilson, S. J. (2011). Mirror neuron system involvement in empathy: A critical look at the evidence. Social Neuroscience, 6(4), 327–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470919.2010.547085

- Corradini, A., & Antonietti, A. (2013). Mirror neurons and their function in cognitively understood empathy. Consciousness and Cognition, 22(3), 1152–1161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2013.03.003

- The “shared manifold” hypothesis: From mirror neurons to empathy. (n.d.). https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2001-01875-002

- Debes, R. (n.d.). Empathy and mirror neurons. University of Memphis Digital Commons. https://digitalcommons.memphis.edu/facpubs/6229/