Imagine you’re at the mall and someone attractive approaches you to ask for directions to the bathroom. Suddenly, your brain turns into a never-ending romantic montage. Every song playing in the mall seems to be about the two of you, and you start imagining what your wedding invitations might look like—even though you haven’t exchanged more than five words. That is limerence. You’re stuck replaying the same 15-second interaction, convinced it’s the beginning of something new, while they were just asking for directions to the bathroom—nothing more. Popular culture often provides examples of limerence, with countless over-the-top characters who are constantly searching for love. Sitcoms, in particular, have offered incredible portrayals of this phenomenon.

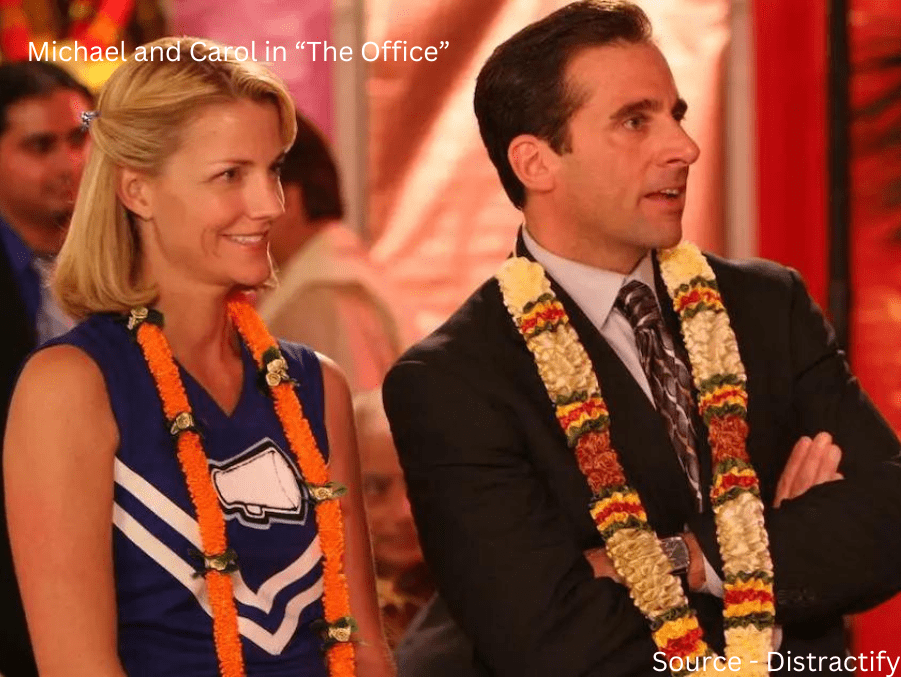

Take the world’s self-proclaimed “best boss,” Michael Scott from “The Office”. He doesn’t have crushes; instead, he imagines full-blown epic love stories in his head. He doesn’t just like someone—he hyper-focuses on them, constructing entire fantasies about their future together. For instance, he photoshopped his face into Carol’s family Christmas card after only two dates. That’s limerence. His brain took a brief interaction and turned it into a romantic narrative far removed from reality.

Michael’s actions are driven by that intoxicating rush of hope, even when his affection is barely reciprocated—or, at times, not even noticed. He misreads signals, like when he believes Pam’s mom is deeply in love with him after a brief fling. He clings to every small moment, every smile, and interprets them as signs of a destined romance. Thus, limerence is an involuntary obsession with someone. It is different from love and lust. It is driven by the need to feel wanted. Instead of building a real bond with the person, limerence fixates on the possibility of reciprocation, often making it a one-sided experience.

Origin of the Term Limerence

Dorothy Jane Tennov, known as Dorothy Tennov, was an American psychologist who, in her 1979 book “Love and Limerence: The Experience of Being in Love”, introduced the term “limerence.” The concept emerged after over a decade of meticulous research, where Tennov analyzed data from thousands of questionnaires, surveys, and interviews. This gave her access to a wide variety of data from diverse backgrounds. Her findings revealed a shared cognitive and emotional experience she defined as limerence—an obsessive attachment to a person, referred to as the Limerent Object (LO), marked by an overwhelming longing for their attention.

Unlike fleeting feelings associated with a “crush” or the stability of mutual romantic love, limerence is characterized by persistent and often involuntary obsessive rumination. These intense feelings can persist for years, driven by uncertainty about the LO’s reciprocation, which amplifies the limerence over time. Tennov’s research helps solidify that limerence finds its grounds through doubt, fueling hope and obsessive thought patterns, making it distinct from love and affection. Further studies by other researchers, like Willmott and Bentley (2015), McCracken (2024), and Wyant (2021), corroborate Tennov’s findings, showing how the uncertainty of reciprocation intensifies limerence, leading to behaviours driven by the need for validation and reciprocation.

The Science Behind the Spark

A possible scientific explanation of limerence would be the existence of the brain’s reward system and the role of dopamine in it. Helen Fisher, an anthropologist, states that the experience of romantic attraction activates key brain regions responsible for pleasure and reward. She explains that falling in love stimulates the same neural pathways as addiction, particularly through the release of dopamine, which triggers feelings of euphoria, craving, and motivation. This dopamine rush not only makes love feel exhilarating but also creates an intense desire to be with the romantic partner, much like how addictive substances generate a need for more.

Given the one-sided nature of limerence and its primary characteristic of uncertainty, we understand that the hope for reciprocation keeps the reward system on high alert, continually seeking the emotional payoff of mutual affection. The brain craves that “reward” of reciprocated love. This intensifies the dopamine-driven loop.

Neuroimaging studies provide strong evidence that “love addiction” and addiction to substances share similar brain patterns. When people are shown images of someone they are romantically interested in, brain scans reveal heightened activity in the reward regions, the same areas activated during drug addiction. These images trigger feelings of love and positive emotions, but they also show how the brain becomes fixated on seeking reward, similar to how it responds to addictive substances (Aron et al., 2005; Bartels and Zeki, 2000; Young, 2009; Fisher et al., 2006). This overlap explains why limerence can feel all-consuming and obsessive, much like an addiction.

The absence of hormones such as oxytocin and vasopressin further highlights the intense, short-lived, and one-sided nature of limerence. Both these hormones play a role in long-term relationships, signifying the presence of commitment and stability. Limerence, thus, is primarily driven by dopamine, which fuels excitement and the pursuit of a reward (in this case, the other person’s attention). This obsessive longing keeps them hooked, much like an addiction, making it difficult to “quit” the person, no matter how much emotional turmoil it causes.

Limerence vs. Love

Now, in order to better understand the concept of limerence, let’s differentiate it from love. The classic Triangular Theory of Love, as given by Sternberg (1986), posits that there are three components of love: intimacy, passion, and decision/commitment.

- Intimacy: Refers to the feelings of closeness and emotional connection in a relationship. It involves warmth, bonding, and a sense of being understood by the partner. In a healthy, loving relationship, intimacy grows over time as partners share experiences and support each other emotionally.

- Passion: This is related to the physical and romantic aspects of love, including sexual attraction and desire. It is the “hot” component that fuels the initial excitement and energy in a relationship. Passion can be intense and thrilling, but it may not always sustain itself over the long term.

- Decision/Commitment: Involves the cognitive choices about loving someone and the commitment to maintain that love over time. It includes the decision to enter into a relationship and the long-term commitment to stay together, despite challenges.

If we apply the same components to limerence, we see that:

- Intimacy: In limerence, the emotional connection and warmth are often underdeveloped. The intense focus on the limerent object usually involves idealized and often unrealistic perceptions of the person, rather than a deep, genuine emotional bond.

- Passion: Limerence is marked by overwhelming passion and desire. The person experiencing limerence has a heightened sense of arousal and infatuation, often obsessively fixating on every interaction and sign of reciprocation. This intense passion is a core feature of limerence.

- Decision/Commitment: Limerence generally lacks the decision/commitment component. While the person may fantasize about a future with the limerent object, there is no real commitment or plan to maintain a long-term relationship. The focus is more on the desire for reciprocation rather than a committed relationship.

What can be understood is that limerence is driven by heightened passion and obsession, but it lacks the intimacy and commitment that are crucial in a stable, loving relationship. Sternberg’s triangular theory helps illustrate that while limerence may feel intense and consuming, it does not encompass the full spectrum of what constitutes lasting love.

Moreover, Aron and Aron’s (1986) self-expansion model of close relationships suggests that individuals enter relationships to enhance their self-concept and increase their self-efficacy. According to this model, people achieve self-expansion by “including others in the self” (IOS), which means that they integrate their partner’s qualities, experiences, and perspectives into their self-concept.

Read More: Self-Efficacy Theory of Albert Bandura

This model differentiates between love and limerence as follows:

Self-Expansion in Love:

- Intimacy and Inclusion: In a loving relationship, the process of including others in the self involves deep emotional connection and mutual growth. Partners genuinely integrate each other’s traits and experiences into their self-concept, fostering a sense of shared identity and personal development. This leads to a balanced and evolving relationship where both individuals contribute to and benefit from each other’s growth.

- Commitment and Long-Term Integration: Love involves a sustained commitment to this process of self-expansion. The relationship helps each partner grow and evolve, with both individuals working together to enhance their lives and selves. This integration is more enduring and mutual, contributing to long-term relationship satisfaction.

Self-Expansion in Limerence:

- Obsessive Focus: In limerence, the focus is primarily on the limerent object and the desire for reciprocation, rather than genuine self-expansion. The limerent person may imagine how their life would be different if their feelings were returned, but this often lacks the deep emotional connection and mutual growth seen in love.

- Unilateral Integration: The process of including others in the self in limerence is often one-sided. The limerent individual may idealize and obsess over the limerent object, trying to integrate them into their self-concept without reciprocal emotional investment. This means that while they may fantasize about self-expansion through the relationship, it lacks the mutual engagement and emotional depth that characterizes true love.

The Hallmark Signs: Am I in Limerence?

Now that we understand the difference between limerence and love, the next question to ask ourselves is whether we are in love or obsessed with the idea of being in love with a limerent object. Understanding the symptoms of limerence would help us. The obvious symptom is that it is all-consuming and uncontrollable. It is characterized by excessive yearning. To elaborate, the factors might include:

- Constant Obsession: Constantly thinking about the limerent object (LO) dominates your mind, making it hard to focus on anything else. These thoughts are persistent and often disrupt daily activities.

- Perfection Projection: You view the LO as perfect and flawless, exaggerating their positive traits while ignoring their flaws. This idealization can create unrealistic expectations and deepen your obsession.

- Constant Reminders: Everyday encounters with places, people, and objects related to the LO trigger thoughts about them. These reminders reinforce your fixation and make it difficult to move on.

- Fear of Rejection: You experience overwhelming anxiety at the thought of the LO not reciprocating your feelings. This fear can lead to avoidance behaviours and emotional distress.

- Mood Volatility: Your mood swings dramatically based on whether the LO shows signs of interest or not. Joyful when they reach out, you can feel crushed and despondent when they don’t.

The Pitfalls: When Limerence Takes a Dark Turn

One of the significant pitfalls of limerence is its potential overlap with various psychological conditions and its tendency to lead to prolonged emotional distress. Limerence shares feature with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), both of which involve excessive rumination and distressing thoughts (Curci, Lanciano, Soleti, & Rime, 2013; Horowitz, 1986). This similarity suggests that limerent individuals may experience intrusive, obsessive thoughts about their object of desire, similar to how those with OCD or PTSD obsess over their distressing triggers.

Limerence is also linked with attachment disorders, similar to what Sperling (1985) described as “Desperate Love,” which highlights how early negative experiences with caregivers might contribute to intense emotional dependence. This suggests that individuals with insecure or problematic early attachments may be more prone to limerence (Ainsworth, 1967, 1973; Bowlby, 1980). Such attachment issues can lead to heightened distress when faced with rejection or lack of reciprocation from the limerent object.

Another major pitfall is its association with Separation Anxiety Disorder symptoms—severe distress related to anticipated or experienced separation from an important attachment figure (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Limerence can mimic the symptoms of separation anxiety, with individuals experiencing intense emotional turmoil when separated from the limerent object.

Moreover, limerent episodes can be notably prolonged, often lasting from 1 to 7 years. These episodes may not end abruptly but can result in extended periods of emotional starvation or minimal attention, leading to persistent feelings of rejection and unreciprocated affection (Tennov, 1979, 2005). This enduring emotional suffering is exacerbated when the limerent object provides only sporadic or mixed signals.

Can We Cure Limerence?

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) effectively treats limerence by addressing its cognitive and behavioural components. CBT helps individuals challenge and reframe distorted beliefs about the limerent object (LO), such as unrealistic expectations that their happiness depends solely on the LO’s reciprocation. This cognitive restructuring reduces idealization and shifts focus away from the LO, promoting a more balanced perspective.

Additionally, CBT uses techniques like Exposure Response Prevention and Behavioral Activation to manage compulsive behaviours and encourage engagement in meaningful activities unrelated to the LO. By gradually reducing rituals and focusing on personal interests, individuals can alleviate the intense emotional swings and obsessive preoccupation characteristic of limerence. Mindfulness and emotional regulation further support this process by helping individuals stay present and manage their emotions effectively.

References +

- Tennov, D. J. (1998). Love and limerence: The experience of being in love. New York: Stein and Day.

- Willmott, Lynn & Bentley, Evie. (2015). Exploring the Lived-Experience of Limerence: A Journey toward Authenticity. Qualitative Report. 20. 20-38. 10.46743/2160-3715/2015.1420.

- Sternberg, R. J. (1986). A triangular theory of love. Psychological Review, 93(2), 119–135. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.93.2.119

- Earp, B. D., Wudarczyk, O. A., Foddy, B., & Savulescu, J. (2017). Addicted to love: What is love addiction and when should it be treated? Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology, 24(1), 77–92. https://doi.org/10.1353/ppp.2017.0011

- Bradbury, P., Short, E. & Bleakley, P. Limerence, Hidden Obsession, Fixation, and Rumination: A Scoping Review of Human Behaviour. J Police Crim Psych (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-024-09674-x